It’s time to land the plane! As we discussed previously, we compared the Impossible Triangle of pricing to the Bermuda Triangle, and the four models for Agentic AI Pricing as the islands you need to land on. To recap:

- Per Agent – You’re paying for access and availability, sort of like hiring a digital assistant. For example, an AI sales development representative that prospect-hunts on LinkedIn.

- Per Activity – You’re metering each action the AI takes (eg. conversation, API call, or ticket). For example, a customer support agent that handles inbound chats (maybe it charges $0.25 per conversation).

- Per Output – You’re charging for finished deliverables (eg. a report generated, a workflow executed). For example, an agentic legal assistant that drafts first-pass contracts.

- Per Outcome – You’re charging for clear business results (eg. savings created, revenue generated). For example, a supply chain optimizer AI that autonomously reduces shipping costs by rerouting freight and consolidating orders (maybe it takes 10% of the savings generated each month).

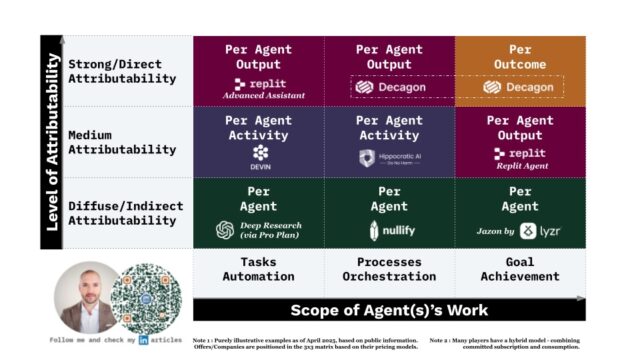

But how do you know which pricing model will work for you? To navigate through the triangle and land on the right right island, you’re going to need a compass! That’s where Michael’s COMPASS Framework (Choice of Optimal Metrics for Pricing Agentic Systems & Solutions) comes in:

Like the instrument panel of an airplane, this diagram may look kind of complicated, but it’s actually quite straightforward in practice. To use the compass, you just need to answer two basic questions.

First: What’s your AI’s “Job”? How does your agent create value?

Is it more like a worker, a service, a utility, or a partner? In other words: Is it doing small, well-defined tasks like “Update this customer’s contact info”? Or is it running a workflow, like “Process a claim” ? Or is it chasing a big-picture goal, like “Optimize this campaign for return on ad spend”?

We call this the “Scope of Agent’s Work.” Imagine a spectrum:

- Task Automation – Think factory line. Quick, repeatable, low-risk jobs. For example, an agent that scans incoming invoices, extracts line items, and uploads them into an ERP system. It handles repetitive, structured tasks quickly and reliably, freeing humans from rote data entry.

- Process Orchestration – Think project manager. Coordinates moving parts across systems. For example, an insurance claims-processing agent that coordinates multiple systems — gathering documents, checking policy terms, routing to adjusters, and triggering payment. It doesn’t just do one task; it manages the workflow end-to-end.

- Goal Achievement – Think of a senior strategist who chooses their own playbook to hit high-level targets. For example, a marketing strategy agent that autonomously manages ad spend across channels, choosing campaigns, reallocating budgets, and designing experiments to maximize return on ad spend (ROAS).

Here’s the second question: How clearly can you prove it worked? How directly can you credit your AI for the desired result?

Picture three people in an office: The executive assistant who makes everything run smoothly but never gets public credit (diffuse). The marketing manager whose work moves the needle but depends on others (medium). The sales rep whose closed deals are logged and celebrated (direct).

We call this the “Level of Attribution”:

- Diffuse (or Weak) – Its impact is real but hard to isolate. It might be one factor among many, or its value is more qualitative. For example, a meeting assistant that schedules, records, and summarizes calls. The productivity gain is real, but hard to isolate from other factors — you can’t easily quantify how much revenue came from “better meeting notes.”

- Direct (or Strong) – Its actions directly create measurable outcomes that are easily tracked, valued, and mutually accepted. For example, a dynamic e-commerce pricing agent that automatically adjusts product prices based on demand, inventory, and competitor moves. Its impact is directly measurable in dollars — higher margins, faster sell-through, or clear revenue uplift.

- Medium – Its outputs are clear, but the link to the business outcome might still be influenced by other factors or harder to quantify precisely in monetary terms. For example, a customer-support copilot that drafts responses for human agents. You can measure faster ticket resolution and higher CSAT, but those metrics are also influenced by team training, customer mood, and product quality — so attribution is partial.

The COMPASS Matrix helps you pick the model that fits both a) what your AI does and b) how confidently you can measure its impact, in order to arrive at one of the four suggested pricing models.

You can see the general shape of the dynamic – on the upper right of the chart, you have a highly attributable, business case-based system. You can charge for quantifiable high-level results. That’s similar to your AE hitting their numbers.

On the lower left, you have a fairly diffuse, automation-oriented system. You can charge for the presence of an agent that handles essential but “minor” tasks. That’s similar to your factory line worker keeping the business humming.

But what about the lower right – A service that is aimed at accomplishing strategic goals, but its impact is hard to prove? Well, if the attribution is diffuse, then the AI is probably enhancing a human being. This is ChatGPT, for example. The outputs may shape executive thinking, but attribution is weak. Hence, per-agent pricing makes sense.

And on the upper left, an example of an agentic AI service with a low scope of work but high-level attribution might be an AI that reconciles expense receipts against corporate card transactions in real time. Each reconciliation directly reduces accounting labor and prevents fraud. The attribution is strong (dollars saved, errors prevented), even though the task is small, so output pricing makes sense.

Finally, here is an important point — no pricing model is inherently “better” than another. Pricing is still about trade-offs. Some models are easier to explain. Some track customer value better. Some give you more predictable revenue. And of course, many companies use a combination of pricing models.

And of course, pricing is never finished. It changes depending on market, product, region, etc. You may need to try a combination of these pricing models. This is a constant process of iteration. But with Michael’s COMPASS Framework, at least you’ll know which way you’re flying. He provides much more context in his LinkedIn post, which I encourage you to read.

Good luck landing your own plane!